Is human-caused climate change as controversial as people think?

May 2019, Robin Quirke

Science does not have a spotless past. As with phrenology and eugenics, there have been instances where science has been used as a way to manipulate people into believing pseudo-scientific “theories” as a way to oppress vulnerable populations. Unlike pseudo-scientific theories, the theory that human actions are significantly altering the climate does not come with power and resource rewards for oppressors. Additionally, the effects of GHG-related human behavior on the climate has been scientifically tested and retested thousands of times, and was a bipartisan belief for decades with mainstream education going as far back as the 1958 Bell Telephone Science Hour’s “Unchained Goddess,” so it is surprising that such a theory has become controversial over the last 20 years.

Nearly split down the middle

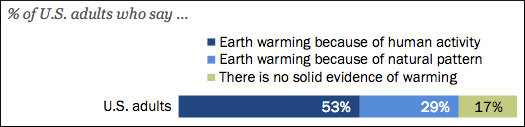

For both 2017 and 2018, Pew found only 53% of Americans think there is solid evidence that climate change is human-caused (Figures 1 and 2), making it seemingly clear that it is a controversial topic, split nearly perfectly down the middle.

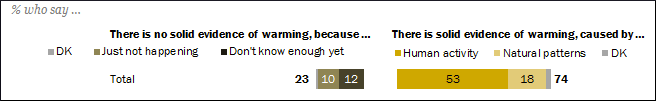

Figure 1. Pew, conducted June 8-18, 2017 (N = 2504).

Figure 2. Pew, conducted March 27-April 9, 2018 (N = 2541).

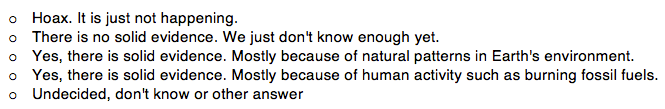

In December of 2017, PolicyInteractive found similar results. We first asked 1103 respondents about climate change, asking them to choose which of the following statements comes closest to their beliefs:

Just 51% chose “Yes, there is solid evidence. Mostly because of human activity such as burning fossil fuels.” Based on this, one might deduce that the other 49% would say human behavior does not make a significant difference to the climate, but when respondents were given a question that captured behavior instead of belief, the theory of climate change as human-caused was no longer controversial.

Is the theory that climate change is human-caused really as controversial as polls lead us to think?

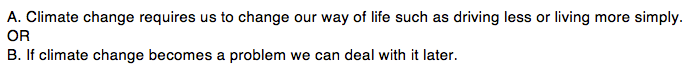

We then asked the same 1103 respondents another question about climate change, this time asking each of them to choose which of the following two statements comes closest to their view:

Although in the previous question only 51% said they think there is solid evidence that climate change is caused by humans, 80% of that same respondent group chose statement A, “Climate change requires us to change our way of life, like driving less and living more simply,” over statement B.

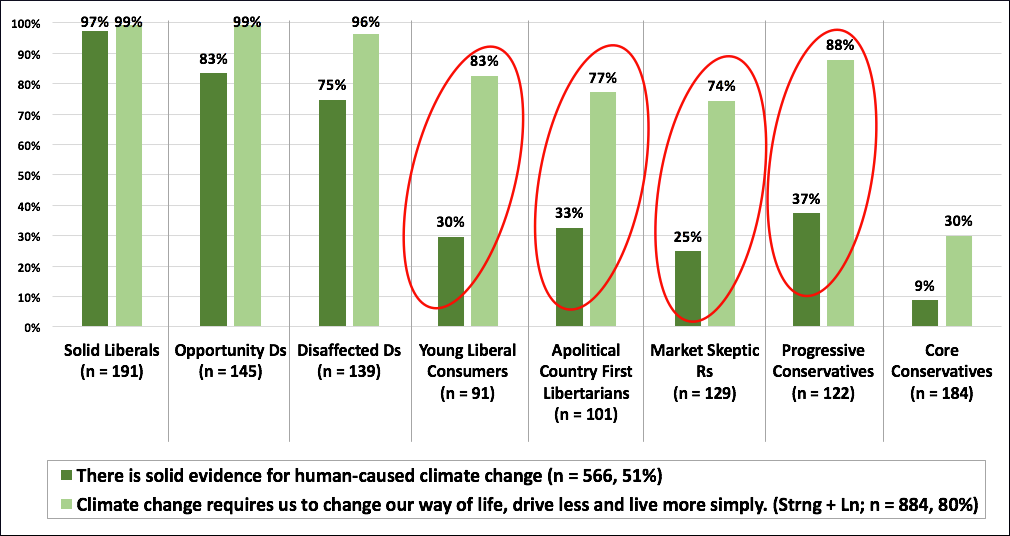

These results can be broken down by voter archetype and side-by-side with the previous question that asked if they think there is solid evidence that climate change is human-caused (Figure 3). The voter archetypes shown below in Figure 3 are organized in order of political leanings, from the most liberal Solid Liberals on the far left to the most conservative Core Conservatives on the far right (see methodology and descriptions of archetypes here).

The dark green bars represent what percentage of people within each archetype agreed that there is solid evidence for human-caused climate change. For example, the dark green bars show 97% of the Solid Liberals and just 9% of the Core Conservatives agreed there is solid evidence for human-caused climate change. The light green bars show what percentage of people within each archetype chose the statement “Climate change requires us to change our way of life, like driving less and living more simply,” over “If climate change becomes a problem we can deal with it later.”

Figure 3. PolicyInteractive, Finding Common Ground Project, December, 2017 (N = 1103)

As shown circled in red, there seems to be a substantial contradiction. For example, among Progressive Conservatives 37% of them agree there is solid evidence of human-caused climate change, while at the same time, 88% of that same group think climate change requires us to change our way of life, like driving less and living more simply.

Beliefs versus Behaviors

Questions that ask about beliefs on climate change might be inspiring political affiliation responding, where people choose the response that most closely aligns with the political party they most resonate with. The forced choice behavior question– should we change our way of life to mitigate climate change or just wait and see if it will be a problem– might force people to be more honest with themselves on the real consequences of human behavior on climate change.

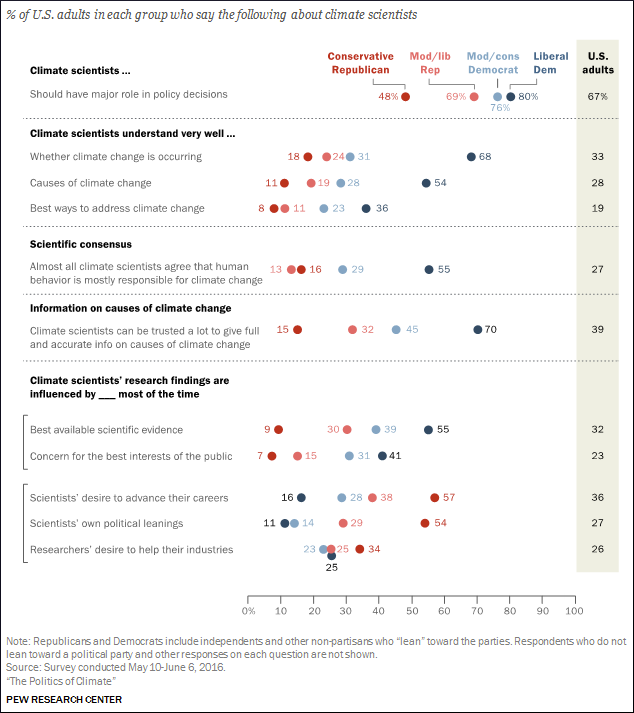

Limited confidence in scientists

Pew Research found that people have limited confidence in scientists– especially climate scientists (Figure 4). Maybe a scientific reference like “solid evidence” triggers a hesitation to agree because of that lack of confidence in scientists. When faced with the option of “If climate change becomes a problem we can deal with it later,” even if there is a lack of trust in scientists, respondents are responding to a basic behavioral option– to change our way of life or to wait until it becomes a problem, instead of responding on their opinions if there’s solid evidence or not.

Figure 4. Pew, conducted May 10-June 6, 2016 (N = 1534).

Comments, questions, inquiries: info@policyinteractive.org

Report by Robin Quirke