Fuel Tax Allocation and the Oregon Constitution

February 2018, Robin Quirke

In September of 2017, PolicyInteractive (PI) surveyed 860 Oregon registered voters, asking them questions regarding climate change mitigation policies. Two of the survey questions explored public support for redirecting a portion of Oregon transportation fuel taxes toward climate mitigation actions, such as improving public transportation and helping people relocate closer to work (thus less distant commuting), showing strong support for this tax redirection. Digging deeper, PI ran a similar survey in November and December of 2017, once again resulting in survey respondents showing strong support for fuel tax reallocation, but when respondents were also informed this would require their state’s constitution to be amended, support for partial fuel tax redirection waned. The following commentary outlines the state constitutional limit on fuel tax allocation and discusses the implications of current public opinion on these issues. Survey was in English only.

September survey showed support for reducing car travel

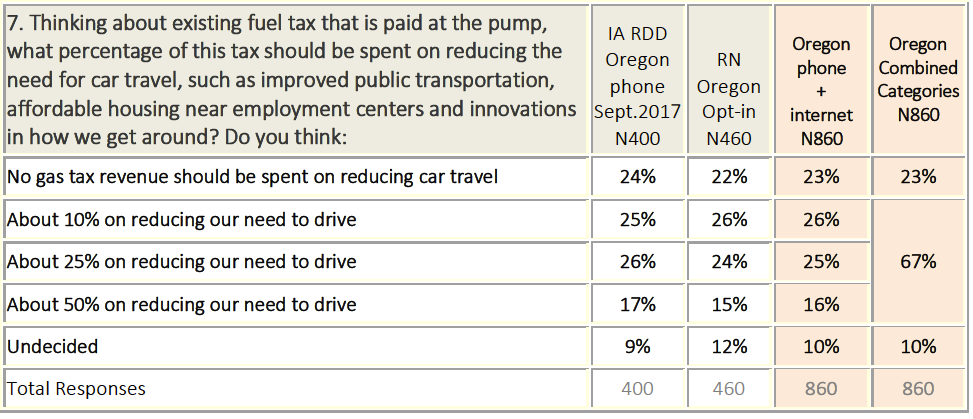

The September 2017 survey found that 67% supported redirecting around 10 – 50% of the existing highway fuel tax going towards investments “reducing the need for car travel, such as improving public transportation, affordable housing near employment centers and innovations in how we get around.”

Note: Sample consists of 400 respondents surveyed via random-digit dial (RDD) by Information Alliance (IA) and 460 respondents surveyed via internet by Research Now (RN).

A closer look

In November and December 2017, PolicyInteractive asked the same question with a different sample of 1103 registered voters from Oregon, Colorado, California, and Washington. These states were selected because each share similar constitutional limits on fuel tax allocation, as well as similar political culture to Oregon. This second survey found 65% supporting at least 10% of the fuel tax going towards reducing the need for car travel. But, when also asked if they would still support this if it required the state constitution to be amended, support dropped to 37%. Of those who did not support amending the state constitution, 41% said the state constitution should be left alone (see full results here; methodology is located at the end of this page). This indicates a puzzling conundrum of support for policy change but lack of will to amend a state constitution to make the change possible. What is the story behind the state constitutional provisions on fuel tax expenditures?

Oregon’s constitutional limit of fuel tax allocation

In May of 1980, Measure 1 passed, effectively limiting the use of Oregon vehicle taxes of any type exclusively to building and maintaining highways. The specific Oregon constitutional language states “[…] use of revenue from taxes on motor vehicle use and fuel […] shall be used exclusively for the construction, reconstruction, improvement, repair, maintenance, operation and use of public highways, roads, streets and roadside rest areas in this state” (Article IX Section 3a). For this ballot measure, 64% of voters voted ‘yes’ and 36% voted ‘no,’ preventing Oregon from using state vehicle taxes for public transportation or carbon dioxide reduction measures, prohibiting funding for any project not directly associated with building or maintaining roads. (Additional report by PolicyInteractive’s Tom Bowerman and 350.org can be found here.)

Measure 1 funded by the highway construction industry

The State of Oregon’s “Summary Report of Campaign Contributions and Expenditures” for the 1980 primary elections reveals that the majority of campaign contributions for Measure 1 came from companies and agencies involved in building and maintaining roads and highways, including the Asphalt Pavement Association of Oregon, as well as several quarry, sand, and gravel companies, all organizations that assuredly stood to profit from such a constitutional limit.

Should highway funding expenditure stipulations be in the state constitution?

The U.S. Constitution has 27 ratified amendments, while amendments adopted “by the people” have occurred in the Oregon Constitution 446 times and has 62 instances of repealing original laws and amendments. The U.S. Constitution has approximately 9,000 words (including the amendments), state constitutions average 26,000 words, and the Oregon Constitution has over 60,000 words. The Oregon Constitution includes details considered by many as inappropriate for a constitution and better suited for a statute book; for example, requirements in elder care facilities and retirement plan requirements for state employees. The Oregon Constitution is an ever-expanding document, not nearly as static as the U.S. Constitution. Initiative and referral activists often prefer installing statutory type policies in state constitutions because it prevents the legislative branch from altering them without a direct referral to a popular vote of the people. However many citizens do not understand this nuance, but rather perceive a state constitution as something of a sacred document that should not be altered. Furthermore, it appears that it is far more likely to add, rather than remove or alter, a state constitution, based on the ever-ballooning size of Oregon’s version.

Moving with the times

However, the U.S. Constitution as well as the Oregon Constitution have been amended as social norms have shifted and laws have changed. In 1857, the authors of the Oregon Constitution did not anticipate that several of the laws they included would one day be considered culturally abhorrent, like the Oregon Constitution’s Article II, Section 2, eventually amended in 1912, 1914, and 1924 concerning right of all majority aged citizens to vote:

In all elections, not otherwise provided for, by this Constitution, every white male citizen of the United States, of the age of 21 years, and upwards, who shall have resided in the State during the six months immediately preceding such election; and every white male of foreign birth of the age of 21 years, and upwards, who shall have resided in the United States one year, and shall have resided in this State during six months immediately preceding such election, and shall have declared his intention to become a citizen of the United States one year preceding such election, conformably to the laws of the United States on the subject of naturalization, shall be entitled to vote at all elections authorized by law.

Although not as astounding as limiting the vote to White males, at the time of Measure 1, voters were not aware of the reality of climate change, and the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The advocacy group Association of Oregon Rail and Transit Advocates (AORTA) has advocated for many years to expand fuel tax allocation limits. In 2011, AORTA proposed the following to Oregon legislators:

- Provide state matching funds for high-speed rail in Oregon

- Provide funds for bicycle and pedestrian facilities outside of road right-of-ways

- Provide funds for intercity bus service, especially in rural areas

- Provide alternative transportation options for those who cannot drive

- Reduce demand on the state lottery for funding Connect Oregon IV

- Reduce demand on the highway network

- Reduce traffic congestion

- Reduce oil consumption

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Methodology

Survey designed and conducted by PolicyInteractive Research, Eugene, Oregon. This opt-in online survey was in English and ran November 30 – December 23, 2017. Two primary respondent sources were used for this survey: 1) non-probability internet sample using the crowdsourcing site Mechanical Turk (N = 504); and 2) internet non-probability sample administered survey with addresses provided by Research Now, a full service marketing and research company based in Dallas, TX (N = 599). Respondents who answered they were not registered to vote or not living in either Oregon, California, Washington, or Colorado were disqualified. All four of these states have constitutional limits on fuel tax allocation.

Full unweighted results and survey questions found here.

PolicyInteractive adheres to the Standards of Practice of the American Association of Public Opinion Research and is a member of AAPOR’s Transparency Initiative.

Comments, questions, inquiries: info@policyinteractive.org